If you walk down Metropolitan Avenue, a street that stretches across North Brooklyn, you’ll eventually reach a dead end: a chain-link fence blocks off access to the waterfront on the East River. But vacant land behind the fence could soon be transformed into a new park that brings green space to the neighborhood—and that helps provide extra protection from storm surges as climate change pushes the water in the river to higher levels.

“We wanted to make a park that really changed the way that New Yorkers interacted with the river,” says Jed Walentas, a principal of Two Trees, the developer that plans to redesign the site, which was once used to store oil tanks for Con Edison, the local utility. Two Trees closed on the deal to buy the site this week.

The new design is part of a development project that will include two apartment towers, with 250 units of affordable housing and 750 market-rate apartments. But a large portion of the land will turn into public space, and some of the riverfront will be excavated so it can fill with water to help reduce flooding. “I don’t know of really any other development projects that actually give up land to allow water,” says Lisa Switkin, a landscape architect at James Corner Field Operations, which is partnering on the project along with Bjarke Ingels Group.

Instead of relying on a typical concrete sea wall next to the shore to protect land from flooding, the design works in part by letting water in. “For us, there was this larger notion of a change in mindset . . . instead of living against the water, living with the water, this idea that’s been prevalent in cities in the Netherlands and other places,” Switken says. “You can’t fight it, so you have to embrace it.”

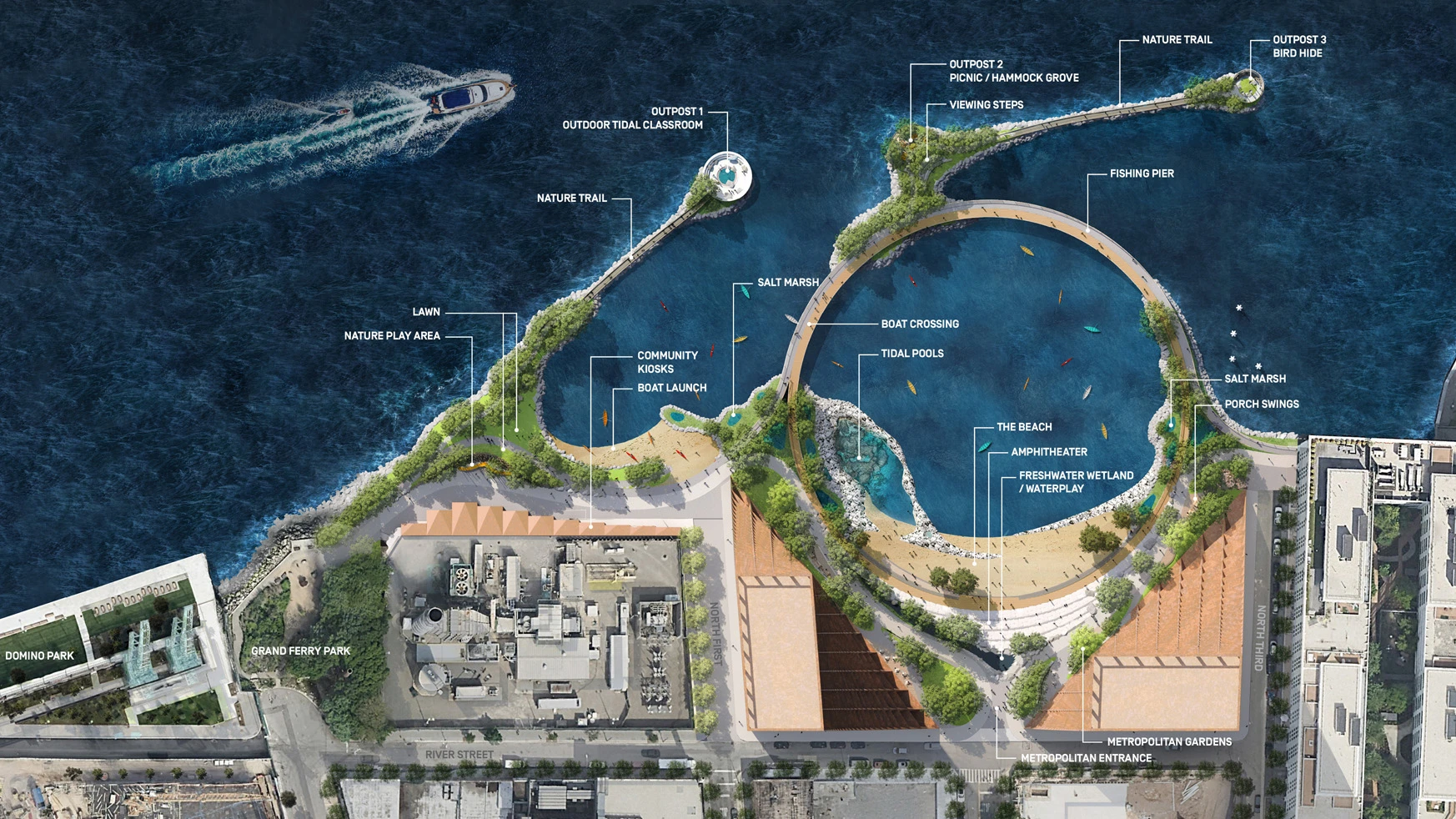

In the proposed design, breakwaters extend into the river, creating partial barriers that can help dissipate energy from waves in a storm. (A hard barrier, by contrast, can’t dissipate waves and can even make them more violent when they rebound.) Paths along the top of the breakwaters lead to an outdoor tidal classroom, a grove for picnics, and another outpost for birdwatching. Inside the breakwater, a series of different habitats help support wildlife, including a salt marsh, coastal shrubs, oyster cages, eelgrass, shallows, and a freshwater wetland, which all also help take the energy out of surging waves and reduce flooding in the area.

A ring-shaped path leads around a cove that can be used for swimming. The East River has been getting steadily cleaner in recent years, bringing wildlife like dolphins and seals back to the area. It’s now safe to swim in, at least when there hasn’t been a recent storm to make local sewers overflow. Over time, the water will continue to become cleaner.

By 2100, the team says, the sea level may rise as much as 75 inches, but the habitats in the park are designed to rise with the water, and the breakwaters can also be built higher.

All of this will provide more outdoor space for everyone in the area—not just those living in the new buildings—and fill a gap in a series of waterfront parks along the river, bringing people to a space that was inaccessible for decades. “By making this part of the waterfront more resilient . . . we’re actually making the water more accessible and more enjoyable to the people living there,” says Bjarke Ingels, founder and creative partner of Bjarke Ingels Group.

The design could also set an example for similar adaptations along the waterfront in other parts of the city and other cities. “No piecemeal approach will make our urban riverfronts more equitably resilient and sustainable,” Henk Ovink, the principal of Rebuild by Design, the resilience innovation competition that first launched in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, said in an email. “The system of riverfronts is like a chain of interdependent links. And while the strength of these chains, of course, depends on their weakest links, the opposite is also true—setting in motion a catalytic change that inspires nearby waterfront developments to adopt the same design approach and raise the bar for urban climate action.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.