The centerpiece of Japan’s delayed 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics, the Japan National Stadium, was intended to reflect a new way of thinking about large scale architecture. The recent decision to ban spectators from the Olympics means that this centerpiece will continue to stand mostly empty even when the games begin later this month.

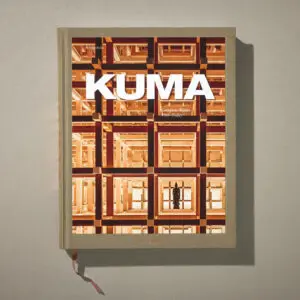

For its architect, Kengo Kuma, the high profile emptiness may not be much of a bother. His firm, Kengo Kuma and Associates, is now one of the most renowned in Japan, and the new stadium, empty or not, is something of a crowning achievement. But it’s far from a typical project for Kuma, whose entire portfolio of work is explored in a new book from Taschen, Kuma, Complete Works 1988–Today, cowritten by Kuma and Philip Jodidio. From its early years, the firm went far and wide for projects, designing in far-flung reaches of Japan and exploring architecture at nearly every scale.

With a focus on materials and applying traditional craft to modern building types, Kuma has established a versatile firm that’s as comfortable designing a major sports stadium as it is devising small civic spaces for rural communities.

Here, in written responses to questions from Fast Company, Kuma explains his inspiration and hope for the Japan National Stadium (designed in collaboration with Taisei Corporation, Azusa Sekkei) and how he sees the pandemic influencing a move away from the “large strong boxes” of urban architecture.

Fast Company: Kenzo Tange’s Yoyogi National Gymnasium, built for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, was one of your inspirations for becoming an architect, and now your new Japan National Stadium has become almost its architectural counterpoint. When taking on this project, what influence did Tange’s building have on your design, and how did you seek to create something completely different?

Kengo Kuma: Kenzo Tange and his Yoyogi Gymnasium are a symbol, or a by-product, of a period of expansion and high economic growth–represented in its high-rise, hard, and masculine design. As for the Japan National Stadium, I aimed to reflect our own time. High growth is now over, with a shrinking and aging population, and people all over the world are paying more attention to conserving and nurturing the environment than ever before. I am moving towards a softer, or more feminine, design in a way, and the new stadium represents that trend.

Your firm launched during the economic bust of the early 1990s in Japan, leading you to seek out work beyond the big cities. What effect do you think that had on your approach to design, and why do you think it’s important for architects to look beyond the big cities and big commissions?

Having worked on numerous projects in the countryside, I began to think about the importance of circulation among architecture, nature, and human beings. “Circulation” became one of my aims in architecture.

Wood is a major element in your work, especially the traditional craftsmanship of woodworking, carpentry and joinery. Why do you think it’s important to keep these traditional forms of building alive in modern projects, even at larger scales?

It is important because large structures start from small structures.

Your work seems to pay very close attention to materials–the GC Prostho Museum Research Center is based on the joints of a wooden toy, and the Komatsu Seiren Fabric Laboratory uses new carbon fiber to improve the building’s earthquake safety. What are the main factors that guide your material choices?

I never decide on materials at the beginning. I keep the discussion going with the client, the local people and all the designers during the process of designing and study the location as carefully as possible to know what material(s) would be most appropriate.

You have had a long and productive working relationship with the small town of Yusuhara, designing a community market hall, a public library and a museum about bridges, among other projects. What makes you want to keep designing projects for this community?

Fortunately, I have been able to build up a firm relationship with the town. I think gaining a sense of trust with people is very important. In the case of Yusuhara, although it was an isolated town in a deep forest of Kochi, the people there are full of pride, and I came to love their spirits. I’ve done my best to meet their expectations.

In the afterword of the book, you criticize the “large strong boxes” that have made up much of the architecture in cities in the late 20th century. If the pandemic is pushing us to think differently about how we live, what new forms do you expect to replace these large strong boxes?

I think that the pandemic has brought about a major ‘model change’ in our way of living, perhaps the first since humans settled in one big place to tend crops and domesticate animals to work. I think people will begin to leave big cities and disperse into many small “bases”–it would be ideal if everyone could have a small base in different locations and move between them season by season.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.