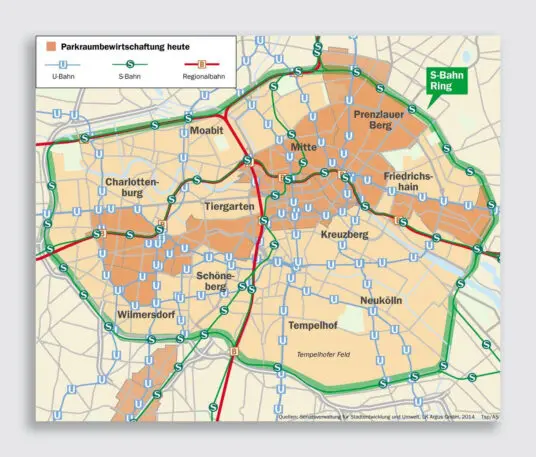

In 2019, at a bar in Berlin, three friends were having a drink when they started considering a radical idea: What if the middle of their then car-centric city became essentially car free? Over the next few months, they kept talking about the idea and eventually created a group: Volksentscheid Berlin Autofrei, or People’s Decision for Auto-Free Berlin. The goal, they agreed, should be to limit cars within the space inside the Ringbahn, a huge circular train line in the city. The space is larger than Manhattan—and if the plan can succeed, it would be the largest car-free area in any city in the world.

It’s already much easier to avoid driving in Berlin than it is even in dense American cities. The trains, for example, run every five minutes. “I don’t even need to know when the next one is coming because I know it’s gonna be soon enough that I don’t care, and that makes a huge difference,” says Nik Kaestner, an American who moved to Berlin in 2020 from San Francisco and now is part of the Autofrei group. (In San Francisco, the BART train runs as infrequently as every 30 minutes at off-peak times.) Most bike lanes are an extension of the sidewalk, away from car traffic, so it’s also easier to bike.

In some cases, people may not be convinced until they see changes happen. Berlin, which was largely destroyed in World War II, was rebuilt with wide, car-friendly streets that look more American than a typical European city. As in American cities, it can be hard to imagine how it might look, say, as bike-friendly Amsterdam instead. But even Amsterdam had to take concerted action to transform itself. While the Berlin campaign is trying to convince as many people as possible to support the idea now, “the goal is not to convince everybody this is going to work before you take the first step,” he says. “Probably what you need to do—and Paris has done this really well, and Barcelona—is to show people through examples what kind of a city you could create, and then to build support that allows you to do it in a more holistic way.”

Already, some neighborhoods in Berlin are building “Kiezblocks,” large areas where traffic is limited, and more are planned. But the campaign organizers argue that the reality of climate change means that streets should be redesigned even more quickly. Kaestner says that people in Berlin are more likely to understand that the answer isn’t just a shift to electric cars. “My biggest takeaway from Berlin, and Europe in general over the United States, is just that they have realized that this is not just a revolution toward electric vehicles, but toward the removal of vehicles in general,” he says.

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.