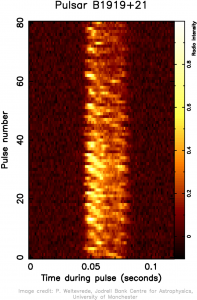

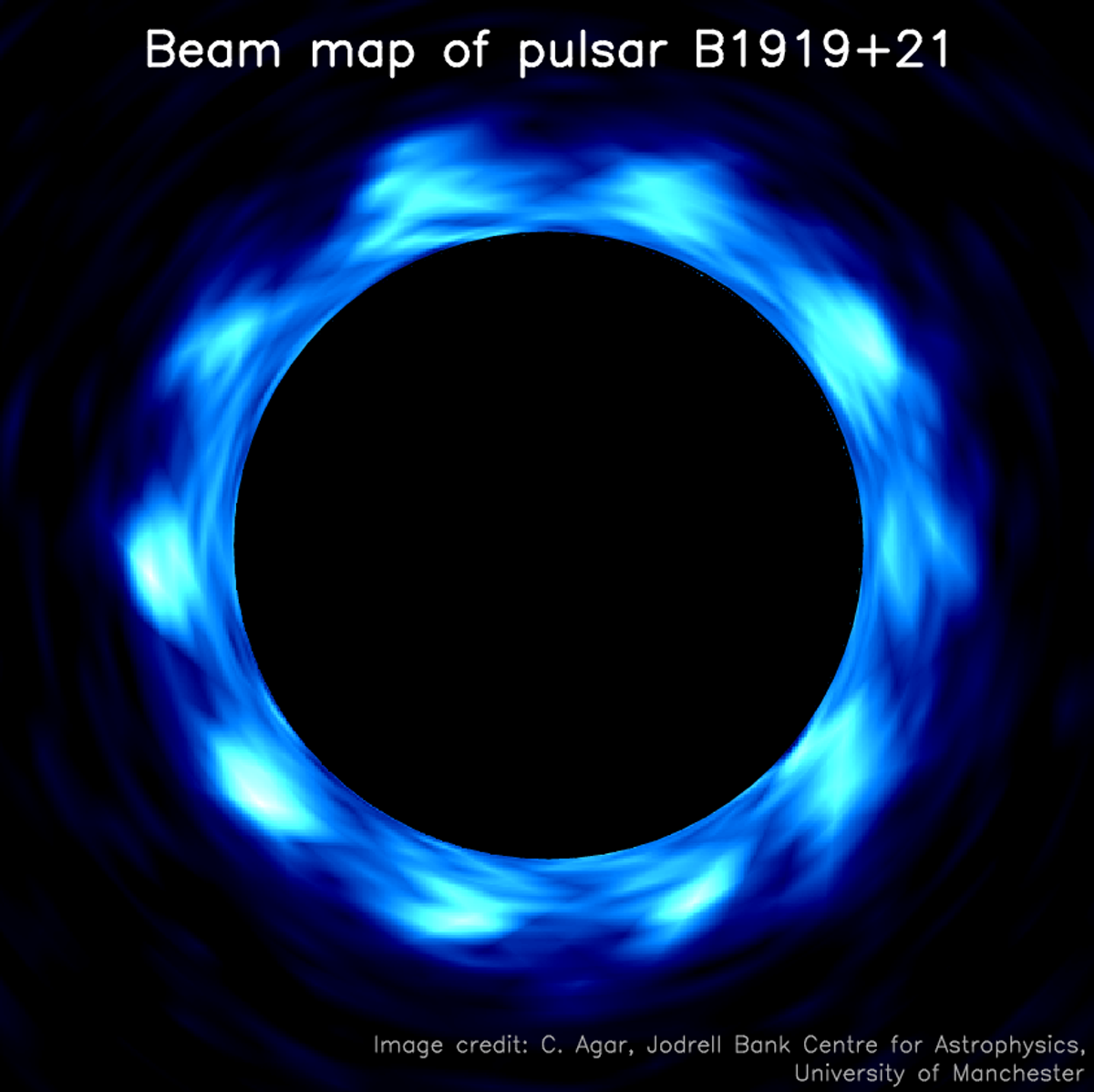

Four decades after the release of the Unknown Pleasures album, we now understand much better what those wiggly lines on its cover mean. But many questions remain about these enigmatic objects, which in many respects are nature’s most extreme creation. Something that remained true for all these years is that pulsar recordings push us to explore the limits of our understanding of the laws of physics.

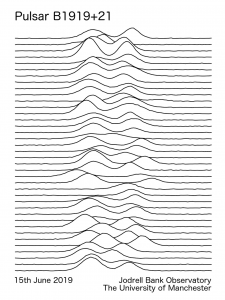

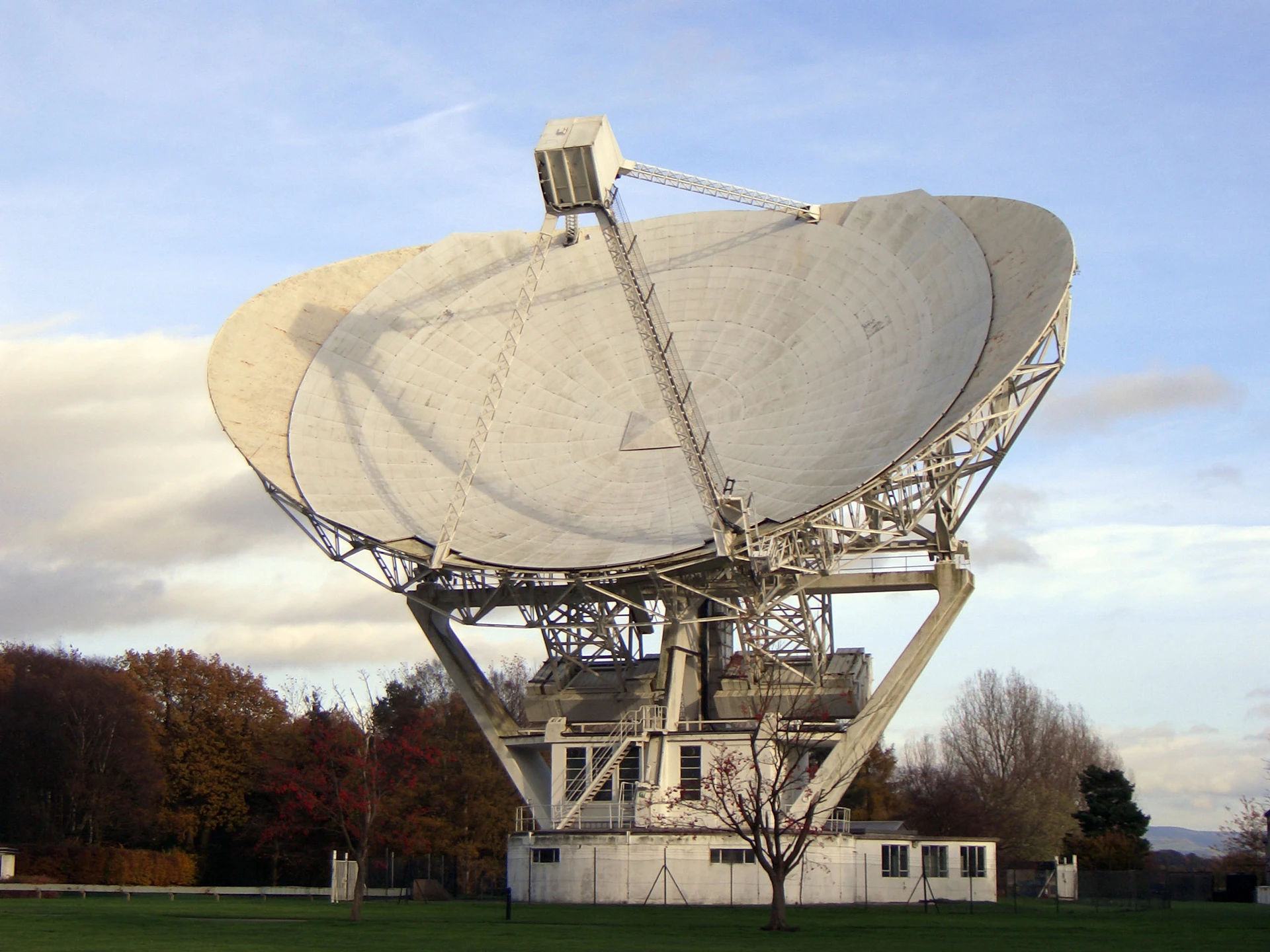

Forty years ago, the English rock band Joy Division released its debut studio album, Unknown Pleasures. The front cover doesn’t feature any words, only a now-iconic black-and-white data graph showing 80 wiggly lines. To put it simply, it’s data from space. To mark the anniversary of the album, we recorded a signal from the same object in space with a radio telescope in Jodrell Bank Observatory, only 14 miles (23 km) away from Strawberry Studios, where the album was recorded.

Some random brilliant record sleeves: Joy Division "Unknown Pleasures" pic.twitter.com/gQVKTEIyyq

— Phil Stanley 💙 (@judgeschneider1) August 7, 2014

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.