If you’re anything like me, you should probably exercise more, read more, budget your spending more, and clean your bathroom more. There are things you want to do that will make you happier and healthier, and yet, it’s all so much. We’re stuck at home in quarantine. And that box of wine is three steps closer than the running shoes.

But what if there were something that could help snap you out of the rut, be it a temporary funk or actual, clinical depression? And what if this something were designed to make doing good things for yourself as addictive as a video game? That’s the premise of The Guardians: Unite the Realms, a new app developed by the Affective Computing group at MIT Media Lab.

[Image: courtesy MIT Media Lab/Affective Computing Group]Sure, there are plenty of apps out there that are designed to nudge you toward healthy behavior, but they don’t work very well. The data shows that people who are depressed don’t want to use self-improvement apps (only about 3% will complete a regimen in these apps). At the same time, people with severe depression still play games as much as people who aren’t experiencing depression. So gaming is a promising avenue for introducing mental health interventions.

Craig Ferguson, lead platforms engineer at the Affective Computing group and game director for the Guardians Project, has studied how software can be more empathetic, and help people improve their well-being. “I’d worked on a couple projects, interventions, [asking] once you detect what’s causing someone to be happy or unhappy, how do you help them? What we’re finding, and it’s no surprise really, is that it’s very hard to get people to do the things they know they should do to improve their lives,” says Ferguson. “I was sitting down to try to think of some way to get people to want to make these behavior changes and form these beneficial habits, and I happened to be thinking about it while playing a stupid mobile game and watching ads for in-game rewards. And it clicked.”

Ferguson then spent years working on an app that could incentivize positive behavior. But he wanted to push beyond a lot of the gamification that’s out there now. He didn’t want to challenge a user to go for a run, then give them a gold star for the efforts—having talked to creators of several such apps, he knew that this approach wasn’t all that sticky in the long-term. He wanted to capture all of the addictiveness that the mobile gaming market cornered. That meant trapping users into an enticing cycle: earning rewards, which let you level up characters, which in turn gets you more rewards, and on and on.

[Image: courtesy MIT Media Lab/Affective Computing Group]Over years of both formal study and informal play-testing in the lab, Ferguson’s app morphed into what it is today, a fantasy land filled with magical animals that attempt to take their world back from an evil villain. Last September, he got tired of the research and started thinking about releasing something—even something still unproven—to help people battling depression. Then with COVID-19 trapping so many of us at home, he made the choice to publicize what was done.

That release, while a fraction of what the game will be in the future, he says, can still take months to complete, and it’s presented with as much glitzy animation and character design as you’d find in any high-end mobile app.

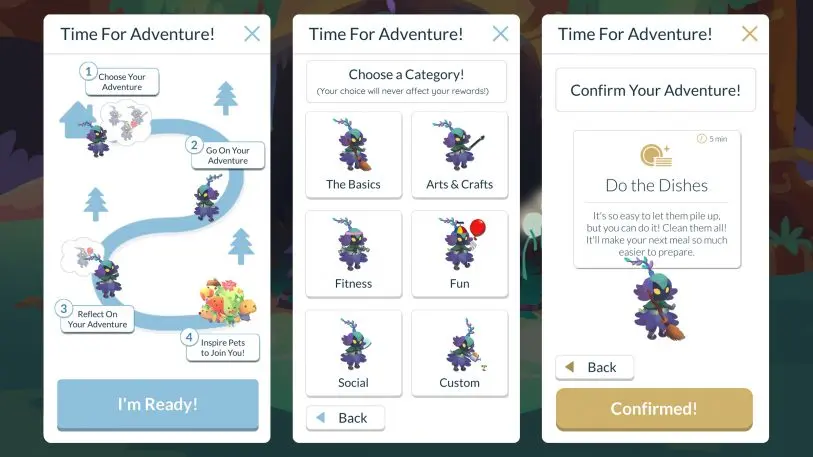

When you load the game, a big button glows and bounces in the upper left-hand corner of the screen, reading “new adventure available.” This is essentially a good-for-you button, because each adventure is focused around the phenomenon of “behavioral activation.” Behavioral activation is a proven therapy that can be used casually or clinically for depression. It gets people to partake in positive experiences rather than spending time doing the things that reinforce their own damaging behaviors. And there are dozens of options to choose from.

Some suggested adventures are practical, such as knocking things off your to-do list that might otherwise cause anxiety: Manage finances. Vacuum. Do Laundry. Others help you grow: Watch an online class. Write a poem. Read a classic. And others help you stay active: Spend time in nature. Learn a new dance. Or, my personal favorite, Jazzercise for 20 minutes.

You are also completely free to make up your own adventure, and repeat it whenever you’d like.

Loading the app in the middle of the workday, I chose one of the easier suggestions: Listen to new music. So I loaded Spotify and tried one of those algorithmic playlists based upon my tastes. It was a stupidly simple adjustment to my day, but it also felt empowering to take steps to break out of my own recent musical ruts. I guess I like classical piano now? Huh!

Once the adventure was done, the interface enticed me like a slot machine, to tap it to unlock several surprise magical forest animals that decide to join me. Then I learned that I could send these animals on tasks, such as foraging for food. They completed a task, then I was offered gold boxes to tap. Confetti sprayed everywhere as I was rewarded in gold and items, and the animals leveled up.

[Image: courtesy MIT Media Lab/Affective Computing Group]

Through the evening, I realize that I’d spent nearly an hour sending my characters on these silly adventures, immediately addicted to the loop of leveling up. But I hadn’t taken on any more adventures of self-improvement for myself. Isn’t that counterproductive?

As it turns out, this structure is completely by design.

Ferguson tells me that an earlier version of the app required these behavioral activation adventures to make any progress at all. “It was a terrible mistake,” he says. “You’d [earn one reward] then you’re done with the app for the day.” The addictive games of the App Store don’t work that way. Instead, they lure you in and constantly incentivize you. Ferguson deconstructed that addictive games trick you by presenting the secondary tasks as the core game. They turn trivial goals into matters of compulsion.

[Image: courtesy MIT Media Lab/Affective Computing Group]So if the core game of The Guardians is about improving something about yourself to get more pets, Ferguson needed to put something else in the way. That’s where the gold and leveling-up loop comes in. Gold has nothing to do with self-improvement, but it entices you to keep opening the app. “And when they open the app to do that, they see that giant shaking, annoying button reminding them to do what they should [which is self-improvement],” says Ferguson.

A day into playing The Guardians, I’m curious if the cost is worth the reward. I wonder if the app pushes me enough toward self-improvement for the cost of being addicted to leveling up some characters in yet another mobile app. Because it is gluing me to my screen, and that’s an investment of my life and well-being, too. (Ferguson does plan to measure the efficacy of The Guardians in a future study.)

That said, if I were the type to constantly play a game like this anyway, there seems to be no reason not to play The Guardians. This game’s design is not serving the bottom line of a company that wants to engage you for profit. The Guardians wants to engage you in your own well-being.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.