To be in contention for the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) crown, you’d better have a powerful punch, sturdy abdominals, and a jaw of steel, and the stamina to fight through blindness, broken arms, and collapsed lungs. But, you’ll also require the resilience to endure an overbearing company that promotes all the league’s players, controls the rankings and belt titles, and pays you a considerably low wage relative to the amount it brings in.

In a market so slim and specific as mixed martial arts (MMA), the UFC consistently emerges as world champ. By most economic measures, it’s a monopolist in the industry and, free of any significant competition, it exercises its dominating power to sustain lower compensation for its fighters. That’s the claim made by six ex-UFC fighters, who launched an antitrust lawsuit against the company in 2014.

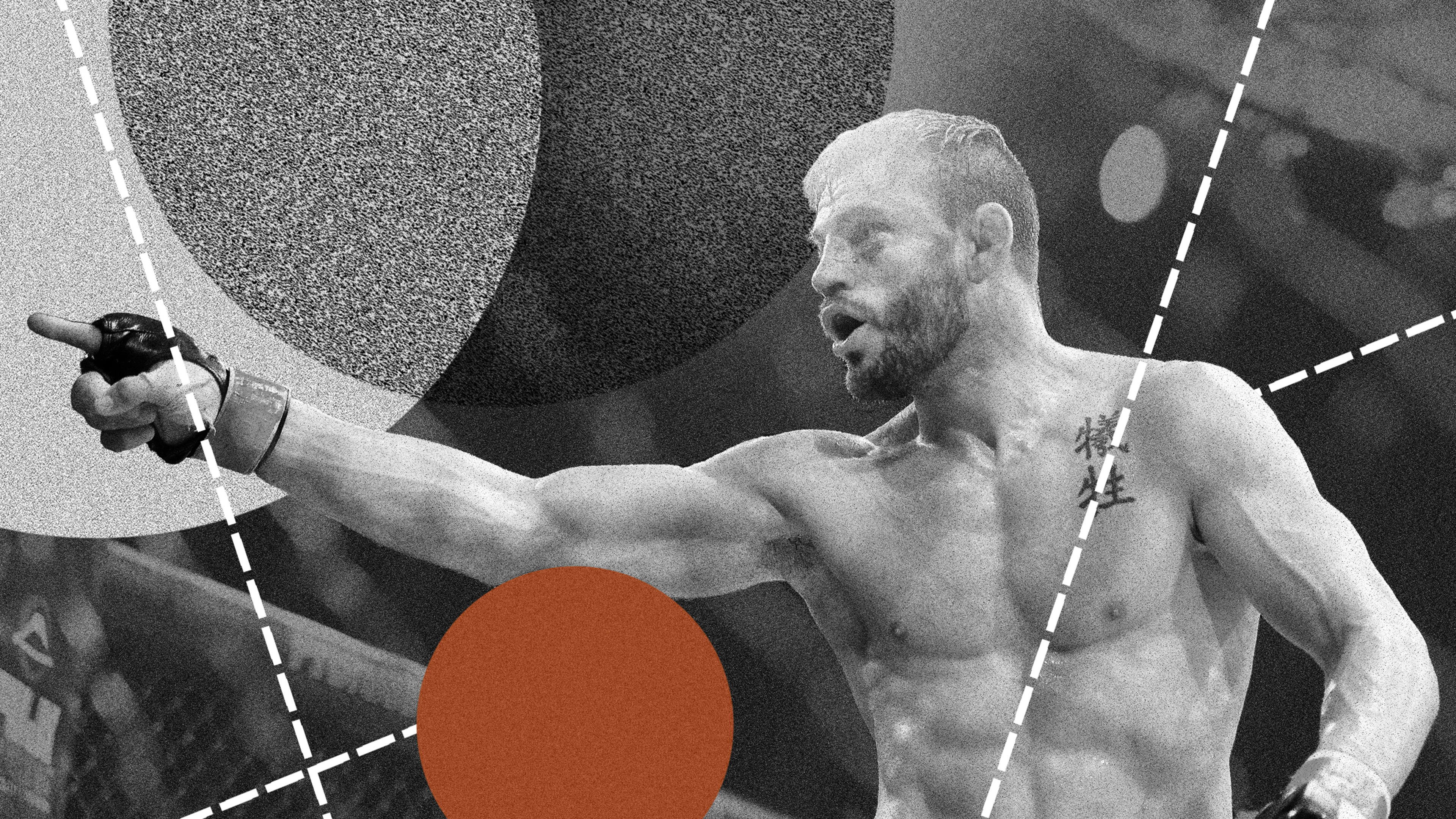

“All I knew was things were fishy, because it didn’t feel like a sport,” says Jon Fitch, one of those original plaintiffs. “Things just didn’t feel right.” The cause of that fishiness was, broadly, a lack of infrastructure that most pro sports have. Unlike in boxing, the UFC serves as the promoter for all fighters, meaning when two competitors engage in a bout, they’re represented—and paid—by the same promoter. Even in the NFL, where that single league dominates, teams are owned by different entities that have independent interests. The UFC also effectively controls rankings and titles, rather than an independent governing body, like FIFA. For Fitch, that means MMA fighters can’t vie for a serious world title. He complains that it even stipulates the required uniforms. “Nascar doesn’t force all the Nascar drivers to drive the same color car,” he says by way of contrast.

The suit is a slow-moving slog, as U.S. antitrust cases tend to be. But, in December 2020, six years on, a judge indicated that he would likely grant it class action status, meaning that, unless they exclude themselves, the 1,200 UFC fighters who participated between 2010 and 2017 would become plaintiffs in the case. On top of damages to correct past undercompensation, which may top $5 billion, the lawsuit is a chance for collective bargaining, absent a union. Because the fighters are independent contractors rather than employees, it’s harder for them to unionize, and past organization attempts have been sternly dealt with by the UFC.

Recognize your brand's excellence by applying to this year's Brands That Matters Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.